"Brian Brooks has been exhibiting internationally since the 1970's with work held in private and public collections throughout Europe, the USA and Latin America. Brian has a natural talent for translating the visual world onto a two-dimensional picture plane. Utilising digital technology and computer software, his paintings use photography as a point of reference rather than a tool for direct imitation. His integral understanding of colour and perspective equals his command for pattern and repetition with an elegant and refined painting technique."

Basia Deptuch

Visual Arts Manager, Curator and Exhibition Organiser

PA to Director of Tate Modern Gallery

Artist statement:

There are three identifiable strands to my artistic practice:

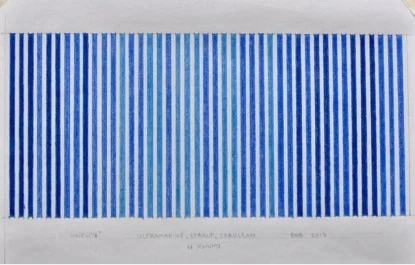

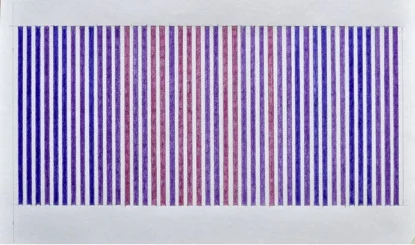

The first consists of colour studies, usually expressed as works on paper to be followed up as works on canvas or linen. These works tend to begin as theories, with a certain amount of calculation, experiment and trial-and-error. This area of work also includes the graphic representations of the colour palettes used in strands two and three.

The second strand addresses possibilities of fragmentation and the simplifying of images into their underlying colours and structures. There is often an inherent playfulness to these works, although they address questions of relativity, luminosity, advancement and recession in pigments.

The third area is the culmination of the previous two, using the building blocks of the colour studies, along with the simplified images, to create paintings with an intensity of approach and in-depth study of the inherent structures, layering and characteristics of an image.

Brian Martin Brooks

'PRV'

Drawings and paintings by Brian Martin Brooks

The title of this series refers to Pattern, Repetition, Variation.

During the late 1960's to the mid 1970's I was a student at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, studying painting, drawing and photography. A main focus of the courses was the Bauhaus movement, as championed by Josef and Anni Albers. Even though I was greatly influenced and intrigued by Albers' teachings on the interaction and relativity of colour, I spent many of the subsequent years concentrating on figurative work, albeit much of this work was referenced by the colour theories that I had been taught and which had led me to further study.

In the mid 1990's, while living and working in Brazil, I began to return to my interest in the Post Painterly Abstract movement, which began in the 1950's and is still (I believe) highly relevant today.

In this series of drawings and paintings I am working with the duality of related pigments to achieve rich coloured images where each can envelope the viewer and create a separate mood. I am also keen to show that in this series each image works with, and reinforces, the other. As the images are halftone, when viewed from an angle or from a distance the viewer's eye blends the colours to form a colour mix that scintillates.

The drawings are colour pencil on Fabriano paper, the paintings are oil on canvas.

Conversation with Clare Brooks - November 2021

CB: I would love to know more about how you started, why you got into art in the first place. In other words, what made you an artist?

BB: Going back to 1955, when I first went to primary school I had already been doing some drawing, like most children do - you know, pencil drawings, crayons, things like that on the floor. I used to always do drawings on pieces of paper on the floor. When I went to my first day at school, what struck me was that most of the children were doing similar drawings. Each drawing was a house with a roof and a chimney with smoke coming out, four windows and a door with a tree on one side of the house and flowers on the other side. And in those days, I remember there would always be a path that went up to the front door, which was always two vertical parallel lines. And two things I noticed was that there was no perspective in the path. And the other thing was that I thought the sky should be a gradation from a darker blue down to a paler blue at the horizon. And maybe I said something or maybe I didn't, but I certainly thought it at the time - that's a memory that stands out.

CB: You were five.

BB: Yes.

CB: A five year old understanding perspective and gradation?

BB: I didn't know the words, but I knew the observation. I knew what something should look like.

CB: And then from that point on, you started drawing and you just continued from there. So what was your representation of a house, for example, what were your first few drawings, do you remember?

BB: Well, I think what I tended to do was not to draw anything from memory or imagination, but I would draw from things that were around me. So if I was going to draw an uncle or an aunt or a still life, I'd want them to be there to be able to draw them, whereas other people would remember what they looked like and do a rendition of them. So I think it was always based on observation. And I think there was a certain amount of escapism as well, because people would visit and I wouldn't really understand the grown up conversations.

CB: And then you went to grammar school and then to art school in New York?

BB: Well, I mean, in the primary school we started off with a head mistress called Miss Edmonds, who was very strict, but she didn't stay very long while I was there. I remember she invited an opera singer to entertain us. And I remember seeing her standing there with tears screaming down her face - either because she thought the opera singer was amazing or because she knew she had to leave. Or perhaps it was tears of joy that she was leaving. And then we got a new headmaster, Mr. Ward, who was very much into music. So I remember we all learned the recorder, I learned the violin. And he would come into a classroom out of the blue with percussion instruments and he'd say, right, you play the triangle, you play the tambourine. And he would get the kids to play these different rhythms and make up music.

When I went to grammar school, my art teacher was Douglas Cox. He was a very interesting artist. I really liked what he did. He would do enormous posters every year for the Christmas shows. And he would create the scenery for plays like Midsummer Night's Dream with help from the students. He was fantastic. And he also got me into photo silkscreen along with various other printing methodologies. As you say, later on I went to art school in New York where by coincidence it turned out that knowing about photo silkscreen was useful, because I got invited to work with Andrew Warhol in the Factory.

CB: What did you do in the Factory? Which era was this?

BB: It was from 1969 to 1974. During my first year at Pratt Institute I was in student accommodation on Willoughby Avenue in Brooklyn and on my floor was a chap called Rupert Smith who was from Florida. And he would throw parties with great music and so on. And so we just started talking one night and for some reason got onto the subject of photo silkscreen and so he invited me down to a party at the Factory on Union Square and that's how I met the gang. And so it went from there.

CB: Do you remember what your first foray into the factory was like, and what were you doing? Were you collaborating with anyone within that group on any artworks, any projects?

BB: Well, the funny thing was that as I mentioned before about doing drawings on the floor - That's the way we used to work. There used to be large sheets of paper or canvas. We would prepare the screens and then squeegee the paint. And so rather than having big tables like Bridget Riley has, for example, it was all done on the floor. So that was kind of an echo of my childhood I suppose. But I do remember some of the projects like Chairman Mao, for example. Andy was always very open to suggestions. One suggestion was, why don't we do a little bit of painting on the canvas. So rather than the whole thing being a machine process, we put a little bit of humanity into there as well.

CB: Oh, and obviously this was an era where he was filming a lot. Were you part of any of these films?

BB: No, I wasn't, but he was filming all the time and I forget the names of all the people he worked with, but he had filmographers and photographers and so on.

CB: Your other passion really is music. So that was a big part of your life in New York too. What happened after the Warhol Factory?

BB: I had been very influenced by a string band up in Rochester, New York, called Jeremiah Peabody. And then I got together with various people in the art school. I put various bands together during that time. When I left art school in late '74, I basically hit the road and just toured although around the same time I was a partner in a music club in the West Village.

CB: So in the years that you focused more on music, you say that you didn't have space for art, but I do remember seeing paintings from the seventies that you did at that time.

BB: That's true. Briefly, I had a really nice studio in an area of Brooklyn called Fort Green. It was an old brownstone and I started off up in the attic on the top floor, sharing it with an architect. And then I found out that the main floor was for rent. So I moved down there, which was amazing. Floor to ceiling windows, high ceilings. I had the main living room where I built a loft and had a studio behind there.

I'd been very taken by the New York Photorealists at the time. People like Richard Estes, Ralph Goings.

A lot of people thought that was a trend that would be over and done with. I was told that many times. But in fact, if anything it's just growing and growing. And this whole idea of when you first see an image, you assume it's a photograph, then you realize that it isn't. It's always been fascinating to me that you have a photograph that's taken in a split second, but then when you draw it and then you paint it, that can take months. And then when you finish the painting, you take a photograph of it. You told me something in French about what they call that.

CB: 'Mise en abime'. When you have something that is related to the thing that's inside it. So it's basically a photograph within a photograph. Yeah. Or a painting within a painting.

BB: Over the years after that I didn't always paint realistically, I would do what I would call semi abstracts using a kind of fragmentation process. With the advent of technology and digitization and so on, it's incredible what you can do now. And what's always fascinating to me is the relationship between the analog and the digital. For example, the human and the machine. And I think there's an integration that's very interesting between the two.

CB: How do you go about identifying objects or subjects or situations that you'd like to paint? There's obviously the process of the concept, right? So you have perhaps an idea, and then you come up with the concept, or is it something that you see around you, like you said in your early years that you represent things that were around you. Is that still the case? And you see things that are around you, so you have an eye I guess for something that you can see, something that could be abstract in a way, that you could zoom into and that will be your focus, your framing of that painting would be that. And then obviously the next process is taking the photograph of that and then making the painting. And then that representation, which is the painting, is representing that concept. How do you come about that concept?

BB: That's an interesting question because there is an aspect where it can be preconceived or something will trigger an idea. It might be a film I've seen or a book I've read, a song I've heard that will trigger an idea and then I'll go out and search for that and take photographs or make sketches. Other times I'm just out photographing and you catalog images or you archive things. I tend to leapfrog. So it might be a series of photographs that I took 7, 8, 10 or 12 years ago or something that I'll go, okay, now is the time. So it's not a linear process where I've got an idea and I photograph it and then sketch it and then do it. I mean, sometimes yes, but very often not.

CB: You have a big bank of ideas in your mind or in photographic form, you already have the images and a series available, you are finding the right time to do them.

BB: Over the years I've been quite eclectic with what I do but it seems like as an artist you're supposed to have a theme that you are researching and exploring. And to be eclectic is kind of weird in a way. I will do landscapes, interiors, still life, portraits, architecture, water, skies, all kinds of things. But to me it's just what's around you and what you think would be interesting to work on. And there's something that you asked me before, where if I had a preconceived idea of what the finished piece would be like, and I think the way I thought about that was you have your initial emotional or intellectual relationship with the image, but then when you start to prepare everything, you're stretching your watercolor paper, you are getting your pencils in order or you are stretching a canvas then it comes to the moment of truth and you are sitting in front of this blank canvas thinking, how am I going to do this? That's partly why we've got this painting here ('Curtain' painting) because to me this is like a deciphering process and I don't think I could have done that without the help of technology. The original curtains where we used to live some years ago were actually brown. Winsor & Newton do a couple of grays that I've always liked. One is called Paynes Grey, which is what this is a version of, but my own mix in oil paint, and there's another one called Neutral Tint. So in order to work out all these different shades, it's actually quite a technical process, which I calculate as percentages of pigment. And this is a prime example of something where I have the whole thing set up and then when it comes to actually doing it, I'm thinking - can I do it? And I just don't know if I can.

CB: So it's a challenge.

BB: Yes.

CB: And that's what really excites you about starting a new project?

BB: Absolutely.

CB: I can tell it's a curtain because I know it's a curtain. But it could be many other things. It could be data streaming, it could be water, it could be many things because of the colour.

BB: I'm very happy to hear that. It's like with songs when they're a little bit abstract. That's why I like people like Bob Dylan. It's poetic, it's got narrative, but it's also quite abstract - you're not exactly sure what it means. So it's open to interpretation, which makes it more interactive.

CB: Great. Well thank you very much. It was amazing to hear all these stories. I mean, I would love to delve deeper into them and perhaps next time we can go deeper into certain aspects of what we've just spoken about. Obviously today's interview was to introduce Brian, his life and work.

BB: Thank you.

Conversation with Katryn Brooks - December 2022

KB: In the 1990s you started doing abstract work. Can you tell me how you got into that?

BB: I wanted to get into work that was about shapes and about colour and about lines and about the interaction of colour. And going back to the 1980s, I had done quite a lot of work with colours of vehicles. This was a continuation of what I'd started in 1974 when I did the Brooklyn Dodge. I wanted to make paintings of vehicles where each vehicle was a different colour, to show how each colour could have so many variations. So, a yellow vehicle, like the telecom van, would have so many different yellows, the red London bus would have so many different reds. And I did a taxi where I didn't want to use black in the painting even though the taxi itself was black. So, I was working through all these different ideas using colour before getting more into the abstract.

KB: So colour was something that you worked a lot with.

BB: It was a central concern, yes.

KB: Especially in oil?

BB: Mostly oil, but also watercolour, pencil, gouache.

KB: Right. But is oil your favourite?

BB: I've done quite a bit of acrylic as well, but to me oil is kind of the governor. I love the transparency of watercolour where you can build up the layers, which you can do in oil as well with glazing. There are so many ways to use different types of materials, it's fascinating.

KB: So you experimented with colour a lot, and then after that, you started doing just pure lines and instead of shapes or representation of work, you started to get away from that?

BB: Doing sort of subconscious or unconscious drawings I thought was quite interesting. I think I've kept some of these doodles. I went through a period where I was doing the Paris by Night series and I did some paintings on commission for British Airways and for EDF. But at the same time I was doing these drawings, some of which I've still got in my portfolio. And little by little over the years I started to convert those ideas or versions of them into paintings, which is pretty much where I am now.

KB: And why did you carry on doing those abstract works - what was it about them that attracted you?

BB: I think there was a sort of a purity to them. I was referencing influences from my foundation year at Pratt Institute, which was very Bauhaus oriented, and certain things reinforced it. I knew about Joseph Albers and Homage to the Square and his work with the interaction of colour partly because of that colour course. That was very much based on his teaching. And nobody had really mentioned anything about Annie Albers. I've always been fascinated by arts and crafts, which refers back to the William Morris era. I saw an exhibition of Annie Albers' work in the Tate Modern a few years ago. Around the same time I also saw an exhibition in Tate Britain of Agnes Martin. So those two things really reinforced what I had been doing with the drawings and experiments with abstract work.

KB: What was it that you were doing?

BB: I started off doing coloured lines on paper with coloured pencils and crisscrossing the lines and seeing how the colours would change or mix when they intersected. And then I just sort of took it from there and just tried different ideas. Some of them are monochrome, but most of them were with colour.

KB: Do you think this is totally separate from your realistic work?

BB: Not really, because I’ve always noticed that if you zoom far enough into a realistic work, it looks like an abstraction, which is basically what it is. I mean, if you're working from a photograph, which I did for years, a photograph is already an abstraction of reality, because for one thing, it flattens it. And the other thing is that it makes choices by framing. And so the person taking the photograph is already very much involved in that image because they’ve chosen that image and they've chosen how to frame that image. So already it's an abstraction. So if you make a painting from a photograph, you could say it's abstracted twice.

KB: Okay. Let's talk about the series that you're doing now. What you call PRV. What does that mean?

BB: IT stands for Pattern, Repetition and Variation. I partly chose the title because I thought of it as being a paradigm for everyday life. You know, all of us have patterns in our lives. We wake up, have coffee, do whatever we do during the day, go to work, come home, go shopping. But also, as an artist, you develop a pattern in the work that you are doing, which you sometimes change subtly or sometimes quite drastically. So that's where the variation comes into it. And the fact that I'm working by hand. I'm intentionally not generally working with masking tape or acrylic paint, but mostly working with oil paint. And so, within the practice of doing what I do, I think variations come in naturally because the hand is always going to produce variations as opposed to a machine. You could work in watercolour or gouache, you could paint with acrylic, but there is something very dense and highly pigmented about oil paint that I happen to really like. Going back to having seen the Agnes Martin and the Annie Albers work, I really liked the fact that it was done by hand and didn't try to be too 'perfect'.

KB: So, what is it about doing it by hand?

BB: It's more visceral than if it's done by a machine. More analogue, if you like.

KB: And in terms of colours, tell me why you chose certain colours?

BB: With this current series - PRV - the first three were based on weaving, where I wanted to show the shading, to try and subtly give an illusion of three dimensionality. And the colours I chose really, were just colours that I found interesting to the point where the paintings would talk to each other, both within and between themselves. So, I tended to go for certain types of green, certain types of violet, certain types of red etc. Then with those three paintings, I reverse engineered the three colour pencil studies, where normally you would do the studies before the paintings. I just decided to reverse the order. Because the studies were so much smaller, I didn't want to put the shading in. So, I just did the two tones rather than the four. And I liked it. I carried on doing five more colour pencil drawings after that. So, I ended up with eight drawings and eight paintings. One thing I found interesting is that each drawing took me about a month and each painting took me about a month. Usually the drawings are much quicker than the paintings, but because of the intensity of the style, I had to work quite slowly to achieve these pigmented effects with the right amount of saturation.

KB: So, by doing the colour pencils you realized that just pure shapes could be more interesting.

BB: Yes. Just the relationship between the two tones of colour.

KB: …was more interesting than trying to represent anything.

BB: That's right. I realized it could work in its own right. It didn't need to look like something else.

KB: Right. So you said you chose colours, which colours have you got in there?

BB: Well I had previously been doing some studies on graph paper with gouache and I'd been working with complementaries, primaries, secondaries and tertiaries because I wanted to get back to the basics of how colours interact with each other. I was comparing the different effects you get when you place colours next to each other. With this series I intentionally avoided the use of complementaries, as I didn't want to create a 'dazzle' effect.

KB: Do you mean that if you have complementary colours they can dazzle the viewer?

BB: Yes, exactly.

KB: Or if you have white?

BB: I wanted them to have movement, but I didn't want them to have bedazzlement. So I was purposely avoiding that. I chose slightly cooler colours, slightly more introspective colours.

KB: So, you can still refer to Op Art but in a different way?

BB: In a slightly more subtle way, perhaps.

KB: Because it's two colours per painting, you chose a combination of colours that were not totally opposite or very contrasting on purpose.

BB: They are versions of the same colour. So, for example, if I used a cadmium yellow as the lighter, brighter colour, then I would use yellow ochre as the darker colour. So, the two colours are related. And I've always been really interested in where colours will move towards another colour. So you'd have a cadmium yellow, which is pretty much central for yellow and you would move towards the red or brown, or a raw umber with yellow ochre. So I wanted to concentrate on what happens with colours as you get movement towards their neighbours. Conversely, if you look at lemon yellow, that's going towards the green. So how many shades could you do where the shades are all recognizable before it becomes a pure green. This kind of movement within colours I've always found fascinating.

KB: By doing this series, what do you want to achieve in terms of the viewer’s experience?

BB: I worked intentionally at a fairly large size, so that if you stood in front of the painting, the viewer would feel like they were enveloped by the colour. That was one thing. Also, we went to an exhibition of Claude Monet works that he did while he was in London in the late 1800s. There was one room where he used a lot of blues - ultramarine, cerulean, cobalt … and the way the lighting was in the room - I’ve never seen this effect before - the light would reflect off the painting back into the room and form a glow. So, I wanted to try to recreate that with this series of paintings where if the light was on a yellow painting, for example, then a yellow would glow back into the room. I was also aware of the science of colour therapy, where different colours have an effect on the mood of the viewer.

KB: Great, but why not use lights then?

BB: I really like to work with materials. I've always been fascinated by materials. If I go into an art supply shop, I can spend hours without even realizing it. I'm just looking at all of the materials and all the pigments that are used and the history of materials, you know, some of which we're still using now, from going back to the cave paintings, the Renaissance and all that. There have been changes over the years, there has been modernization and acrylic is a prime example, with more factory or laboratory-produced colours . But I just like the physicality of working with materials. It doesn't matter if it's graphite or if it's ink or if it's paint or whatever. I just really like that.

KB: So for this series, you want people to experience the paint physically?

BB: Partly that, but I also think there's an aspect of when a viewer looks at the work, they can't help but think about the fact that someone has spent that time doing it. If you work with light, I’m sure you are conscious of the fact that someone has set this up and they've experimented with it, and they've seen how it works and the effect that it has on the viewer. I mean, Dan Flavin for example, the neon lighting that he uses - fluorescent lighting. There must be a lot of experimentation and thought that goes into that. So as a viewer, I'm sure you are aware of that. Whereas if it's a painting, I'm sure you are aware of the fact that an artist has been in front of that painting with a brush. And this gets on to the topic that we had mentioned before about reproductions. To me, there's no way that a reproduction can be the same as viewing a piece 'in the flesh'. I read recently that you tend to 'read' a reproduction, whereas you tend to really look at and experience an original piece of work. There's a physicality to it.

KB: So the viewer is immersed in the colour through paint, rather than through light or by any other means. So it is about the power of paint actually, isn't it? And not only that, but there are optical effects in the paintings, which I found very engaging. You look at the painting for about a minute or so and your eyes start to wander because you haven't got any focal point. And your eyes start to see different patterns. Sometimes when you focus your eyes on a specific area I had the impression that in that area the squares were appearing to expand, and this created very strange optical effects as my eyes moved through the painting.

BB: Well, I mean this has been studied for websites. How people's eyes move. So, the way I was brought up was, you know, very post-Victorian where there always had to be a point of central focus, a focal point, and perspective - very Renaissance in a way. And part of the Bauhaus training was to think about the overall effect of images, which I’ve very much done with this series. They are very much overall works. When I took my foundation course, we were given pieces of dowel about an inch in diameter that we cut about two inches long, We had a pot of black ink and a sheet of newsprint, which is cheap recyclable paper for newspaper. Every day we were supposed to add one round black dot until we had built up the whole page. We were encouraged to explain why we'd chosen where to put each dot. That was the hard part! Here there's no one point that's more important than another. Therefore, the eyes tend to move around because they don't really know where to stop, where to focus. It's almost like you are looking at yourself, looking at something, which I find psychologically quite interesting. I find it absolutely fascinating that each person that looks at an image will have their own interpretation of it. So you were talking about looking at these coloured squares and your eyes moving around and the squares getting larger. What I see in them, is the squares actually forming shapes. The shapes are usually lozenges and the lozenges kind of pulsate and move around within the image. So, this is very much a subjective aspect that I find interesting in terms of what the viewer perceives. Whereas if you do a realist painting of a vehicle, for example, the viewer's going to be looking at the window, the door handle, the wheel, the hub cap, the headlight, the tail light - whatever's shown in the picture, the viewer will look around at things that they recognize. What intrigues me with the abstract is, besides the fact that it's coloured squares, there's nothing that they recognize. So they start to do the work themselves to try to find shapes and images within the painting itself. And I find that quite interesting in that the viewer is more active, I think.

KB: Yes, it's more interactive. Thank you, Brian.

‘CURTAIN’ Project

‘Liminal – relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process.

Occupying a position at, or both sides of, a boundary or threshold.’

(The Oxford English Dictionary).

I began this project for a number of inter-related reasons - some practical with others philosophical.

As an artist, one finds that rather than progress being linear, it tends instead towards the cyclical. I actually began exploring the ideas for this series whilst living with my family in Kent, in the South of England, between 2001 and 2006. Opening the curtains could reveal nature or the man-made urban environment. Closed curtains would always harbour a sense of expectation for what they would reveal on being opened.

To address the practical questions for this project first, I have spent a number of years searching for a link between the on-going colour studies and the resolved, objective oil on canvas/linen paintings. In this respect, the ‘Curtain’ series explores an area between objective and non-objective. I’ve always felt that the colour studies are a necessary preamble to the better understanding of colour mixing and relativity, light/shadow, advancement/recession along with dealing with questions of creating an illusion of three-dimensionality, as opposed to interpretations of the intrinsically ‘flat’ photograph.

In this respect, the curtain series is a first celebration of finding what I might term the ‘missing link’.

Another question I wanted to resolve was the possibility of working to a minimalist format, along with the exploration of a variety of inter-related mediums – in this case graphite, colour pencil, watercolour and oil on canvas. This series also opens up possibilities of printmaking. In order to address the minimalist question, I decided to work with a single image, rather than inter-related images, exploring a range of colour and grey-scale possibilities.

Moving on to more philosophical questions, the more I thought about this project and subject matter, the more I realised the inherent meanings in the image itself.

Curtains are a paradigm for beginnings and endings – of a light cycle, for example – opening curtains at the onset of morning, and closing them as the light fades. There is, perhaps, a parallel with the beginnings and endings of life.

Curtains both hide and reveal – pertinent, therefore, for the visual artist, in that the images an artist chooses to work with are thus revealed to the viewer, having gone through a process of investigation, filtration, manipulation and editing.

Certain ironies are manifest in this series. One encounters the perennial dilemma of the interior designer: whether to choose the décor to ‘match’ the artwork or vice-versa? The artist draws a curtain, while the final piece may be whimsically titled ‘the final curtain’. The placing of a painting of a pair of curtains on a wall could give the impression of a ‘window’ behind them.

The choice of colours for this series is potentially practically limitless, but I have narrowed these possibilities down to the basics of colour separation found both in printing and light.

Colour Frequency

This series is based on a simple algorithm. An algorithm is a procedure or formula for solving a problem. The word derives from the name of the mathematician, Mohammed ibn-Musa al-Khwarizmi, who was part of the royal court in Baghdad and who lived from about 780 to 850. Al-Khwarizmi's work is also the likely source for the word algebra.

A computer program can be viewed as an elaborate algorithm. In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm usually means a small procedure that solves a recurrent problem.

With this series of studies, I use a system of (3,2,1 / 1,2,3) limiting myself to three colours for each drawing. I am unable to predict the visual outcomes without carrying out the studies, which are completed in colour pencil, watercolour or gouache on paper. The results will then be scaled up into larger paintings rendered in acrylic on primed linen.

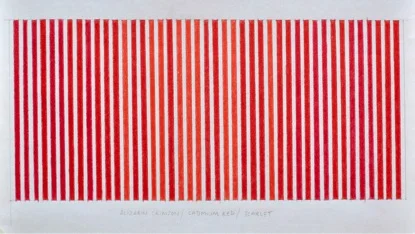

Study 1: Three Colours (Red) (Alizarin Crimson, Cadmium Red, Scarlet): The use of three colours, as in this example, produces a colour shift by one factor. In this instance, alizarin crimson (the first colour) begins the sequence, but cadmium red (the second colour) completes it. As one colour decreases in frequency, the following colour increases, producing an overlap. For how long would the cycle need to be repeated before being able to end with the first colour?

Study for ‘Three Colours (Red)’ – colour pencil on paper – 127 x 277 mm.

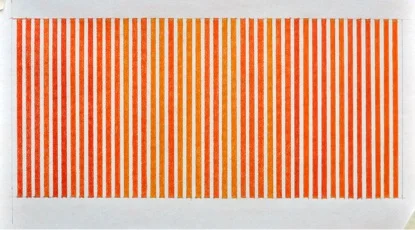

Study for ‘Three Colours (Orange)’ – colour pencil on paper – 127 x 277 mm.

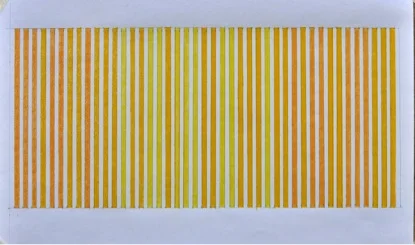

Study for ‘Three Colours (Yellow)’ – colour pencil on paper – 127 x 277 mm.

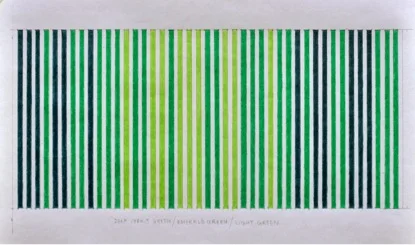

Study for ‘Three Colours (Green)’ – colour pencil on paper – 127 x 277 mm.

Study for ‘Three Colours (Blue)’ – colour pencil on paper – 127 x 277 mm.

Study for ‘Three Colours (Violet)’ colour pencil on paper – 127 x 277 mm.